Articles

Art & Controversy

The room was packed one night for the main performance at The Indie Armchair Theater in Cape Town. Everyone sat on the floor facing a big wall with a blank white canvas hanging from it.

The artist everyone came to see was an experimental painter, who this night would paint free-style to the sounds of live, improvised music coming from the band to everyone’s left. Nobody knew what the canvas would look like in the end, not even the artist.

A brush of red here and there to start out with, a blotch of blue thrown randomly a few minutes later when the drummer crashed the cymbol. With animated bodily movements, he later started pouring paint directly from the bucket over much of the incoherence he’d ‘painted’ till then.

The music ended. He apparently had nothing more to express. The show was over. Everyone applauded as if they partook in a spiritual ritual. Had you pointed to the canvass and asked, “But what does that mean?” people would look at you funny.

Part of the post-modern mindset is to look at things with an even eye. One artwork is as good as any other. It’s entirely subjective. A cacophony of electronic noise is as good as an ingenious classical composition. Rembrandt’s eye for proportion, symmetry and his ability to capture a scene with mathematical precision could be displayed next to a canvas decorated with splashes of paint, thrown at it at random, with no intent, meaning, or skill. The two pieces would be considered artistic equals. Some would prefer the splashes.

I believe part of it has to do with attention span. It takes time to appreciate what made Rembrandt an objectively better painter than most – time people don’t have or care to spend. As a result, everything gets an equal glance. Nine seconds by which to judge expertise that took thirty years to develop.

There’s no more awe because we don’t pay enough attention to realize what we’re looking at, listening to; what we’re smelling.

From Good to… Anything

Art underwent a radical move away from craftsmanship and skill to the realm of ‘expression’ or directly into meaninglessness or the ‘abstract’.

With abstract works, you’d find yourself staring at a piece not because you’re wowed by it but simply because your mind looks for patterns, meaning, or intent where there is none. That’s a different kind of captivation compared to Rembrandt’s work, where you appreciate both beauty and skill – you can’t help but wonder at the scene he captured because he captured it so skillfully. You’re wowed, engaged by the artistry (and the human capacity for it), whether you like the piece or not is almost beside the point.

But it’s moved beyond even the abstract. Fame and fortune now is gained, not through genuine artistry or prowess, but merely through spectacle.

Get enough people to see you fail at tuning your guitar and you’ll have more fame and money than an accomplished musician.

Andy Warhol’s canned soup showed how statement pieces taking over skilled creation meant that the statement became the product – no longer did the artwork itself make the statement, nor did it have to be any good. A picture of a banana does the job as well as any intricately composed artwork could… because it’s not about the art but the statement.

It felt liberating. Everyone could suddenly have a say because anyone could have said what ‘the artist’ said in the first place. Pollock started a revolution essentially the same way.

Always a Controversy

Great art can be controversial because it first inspires awe, then challenges people with its message. It’s because Caravaggio’s lost work “St. Mathew and the Angel” was such an exquisite painting in the first place that people protested its meaning.

Art has the power to bring people together as much as it has a way to divide. Both are possible because of our personal attachment to art; that we recognize it has the capacity to shape culture. It has already shaped the culture you’re in so that when a piece comes along to challenge your comfort zone, it’s speaking to you directly.

(How many books – or podcasts – have been burned or banned throughout history under the pretense they threaten the prevailing culture?)

“The Gross Clinic” by Thomas Eakins was not allowed to be displayed at first, despite being an incredible show of painting mastery. At a time when medicine was making strides, it showed people a vivid image they may not associate with ‘progress’. Eakins’ piece was so well done that exhibitors knew it had the potential to challenge the prevailing milieu.

In 2009, Chen Wenling’s work “Bull Fart” (a.k.a. “Bernie Madoff’s Bull”) was, at first glance, your typical post-modern spectacle with no meaning. On second glance, a flying bull goring Bernie Madoff, and then on a third glance the show becomes quite a sophisticated indictment of the financial crisis at the time. The work enjoyed controversy aplenty because it first awed you (how do you look away from a massive bull rocketed into the air by its own gastric jet fuel goring a notorious financier?), and it was packed with meaning.

When Metallica teamed up with the San Francisco Symphony, I’m sure many classical performers couldn’t stand it, but they probably gained some respect for the band’s instrumental virtuosity. But more than that, the controversy came from the content itself – the fact that the clash-of-cultures-collaboration… worked.

“Honestly, the closest I can think of them, as well made as they are, with actors doing the best they can under the circumstances, is theme parks…”

“It isn’t the cinema of human beings trying to convey emotional, psychological experiences to another human being.”

The above is Martin Scorcese’s take on Marvel movies. Francis Ford Coppola went on to call them “despicable”. In Marvel’s defense, Mark Ruffalo says:

“When we look at the box office [of] Avengers: Endgame, we don’t see that as a signifier of financial success, we see it as a signifier of emotional success. It’s a movie that had an unprecedented impact on audiences around the world in the way that they shared that narrative and the way that they experienced it. And the emotions they felt watching it.”

At least the controversy is still rooted in creative output – both Scorsese’s movies and the Marvel universe required skill and competence to make, no matter what you think of the artistic merit of either.

But when spectacle fuels the engine in our times, controversy is often sought out for its own sake. Yoko Ono daringly invites people on stage to [daringly] cut off a piece from her clothing, or the latest female talent shaking her naked hips – it’s less about the music and more about the spectacle they put on.

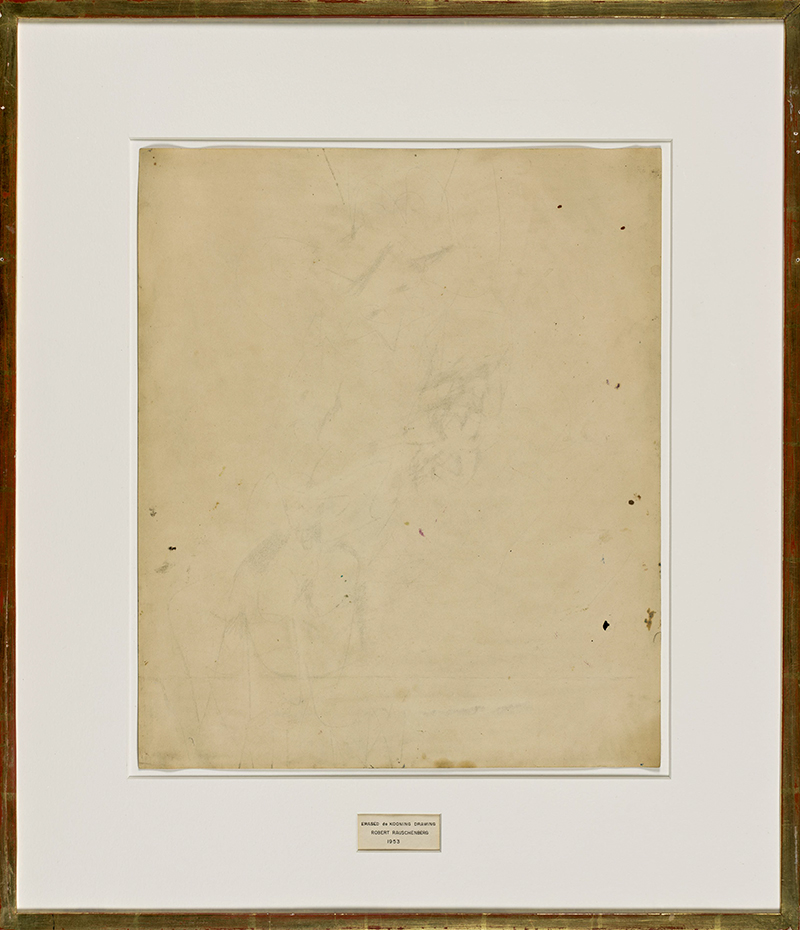

Remember how Marcel Duchamp’s toilet made a splash in the art world or how Salvatore Garau sold an invisible sculture for $18,000, or Tracy Emin’s “My Bed” at the Tate? – more of those ‘statement’ pieces that were controversial but where artistic genius is not what was on display; where someone ordinary showcased something ordinary.

Sanctioned Rebellion

Philipp Glass can explore discord and record 4m33s of silence and call it a song because he is first known as an accomplished composer and pianist. Likewise, Anthony Braxton or Coltrane disrupted conventional harmony meaningfully.

They knew the correct scale progression but deliberately played the wrong one at exactly the right time (and composed avant-garde songs around what seemed to be disharmony). A classic case of knowing the rules before you break them.

John Zorn has every jazz musician’s permission to make an album using his sax to mimic duck calls make because he’s one of few who knows his instrument well enough to get those sounds from it. To everyone else, the album would rightly be scolded as mindless quacking.

Mehmet Ozcay captures half there is to learn about calligraphy in a single letter, perfectly written, because he has spent thirty years chiseling away at his craft. He made it look so easy that he inspired a new generation of modernist and minimalist calligraphers who created similar refrain pieces using single letters. The difference is they glossed over their first thirty years of training to the extent that their work qualifies as little more than statement pieces, not the work of master calligraphers.

To me, Michelangelo’s ‘Last Judgment’ is a hideous abomination, while others don’t mind the vulgarity of it – rather, they praise it, get lost looking at it. Either way, you can at least appreciate the artistry – the skill – required to execute that show of obscenity.

They may be of varying aptitudes and tastes, but they are all true creative artists, controversial as their work may be. Not people who make statements or who pose abstractions or enact spectacles in search of fame.

Crime & Punishment

There would always be some subjective bias and personal preference for one song over another, but you’ll never be able to convince me that Bieber is a better musician than Beethoven. That Da Vinci had an eye for detail combined with the ability to execute his vision in a way Andy Warhol could never have done is not a debate anyone would get into and expect to win.

It’s in this sense that EO perfumes are ‘classical’ more so than modern. Some modern perfumers throw a bunch of aromatics together and call it a work of art in the way our friend the experimental painter did when he wasted all that paint to paint nothing at all.

‘Classical’ in the sense that there are parameters. You don’t add hay absolute to vanilla because you’ll have a mess on your hands. Unless that mess is your statement piece, you’ve wasted your hay, the [expensive] vanilla, and your time.

Unless you know using seven different ouds will have a certain – meaningful – impact on the composition, don’t make “7” your statement piece. If adding more than x% rose otto kills a CO2 agarwood extract, either don’t use that much rose or opt for a bolder hydro-distillation in its place. If adding anything more than 30% frangipani won’t make your perfume smell anything more like frangipani, don’t use 50% just because you can boast that you did so.

And, most certainly, don’t blindly throw your atelier at the canvas, bottle what comes out, and call it ‘artisanal’ – or worse, ‘a post-modern expression of olfactory chaos.’

“Painting is easy when you don’t know how, but very difficult when you do.” – Edgar Degas

Obviously, I’m not comparing my perfume work to any of the artists mentioned above, but you can’t help but hear the echoes of controversy and see the filters different people apply to reach their judgments.

Some judge a perfume solely by how long it lasts or how loud it is. The smell of black kinam, in that sense, would not be worth much if the experience doesn’t last long or if you have to bring your nose right to the tip of the heater to get a whiff, even though one whiff is worth more than a hundred perfumes that last for days.

Blue lotus or sandalwood fragrances will never be ‘loud’ in the same way you shouldn’t expect the most exquisite tuberose to last for 8 hours. Yet, these are among the most precious and intoxicating aromatics on Earth.

Art & Obsession

“Reading so exciting it knocks you out of your armchair!”

Crime & Punishment has split the community right down the middle. One half is trying to figure out why it doesn’t last as long as they believe it should or as long as other EO perfumes, while the other half is in love with it and praise its projection and longevity.

I can objectively deconstruct the composition of C & P and explain how it contains a list of the world’s most sought-after ingredients, how it was composed in similar fashion to other EO perfumes and the carrier is deer musk at a similar or higher concentration than other EO perfumes which do not enjoy the same degree of controversy. And compared to the OG, aside from the additional musk, they are 99% identical. So, yes, that this particular perfume should once again stir up such dispute is fascinating.

But it’s the passion with which both sides make their case that’s so great to behold. Contrary to the dictates of modernity, many people I know take perfume seriously and spend quality time to appreciate fragrance and refine their olfactory acumen.

They feel passionate enough about a fragrance to let their bottle of Crime & Punishment sit for two weeks before applying it to make sure they give it an honest assessment. Some spray their bottles once and then leave them for months before they start to use them. They do so based on know-how, not superstition, and interest.

This obsession, the constant reappraisal, the back and forth, the spraying it on friends and family and colleagues to get their feedback, spending time on long threads trying to get down to the bottom of the matter…… these are all signs that you’re dealing in art, and that you’re a patron of the arts even if you didn’t realize it. Ask any art collector – they suffer from the same beautiful obsession because they care enough about it.

And for this, I am thankful, and for that I will continue to do my best in order to bring you not a statement but a carefully thought-out, meaningful – and yes, possibly controversial – work of olfactory art.